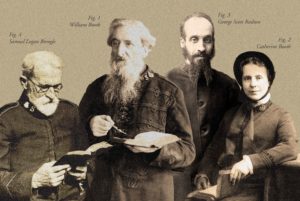

4 Key Salvation Army Biographies

4 Key Salvation Army Biographies

That Uncover Our Treasures

Part 2: Catherine Booth

Booth-Tucker, Frederick de Latour. The Life of Catherine Booth, The Mother of The Salvation Army, 2 Volumes: New York: Fleming H. Revell Co., 1892 [Vol. 1]; London: The Salvation Army, 1893 [Vol. 2].

Frederick de Latour Booth-Tucker’s biographical account of Catherine Booth, entitled, The Life of Catherine Booth, The Mother of The Salvation Army (Two volumes), is considered as one of the most authoritative biographical works on Catherine Booth (1829- 1890), “the Mother of The Salvation Army.” Although this biography of Catherine Booth in two volumes contains the hagiographical elements, the virtue of this biographical accounts of Catherine Booth should be credited in terms of preserving the rare collection of firsthand materials related to the life and ministry of Catherine Booth. Those are including the collection of various types of letters she had corresponded with significant people including her husband, William Booth and other immediate family members, and some pieces of her sermon materials, notes from her diary, and her written addresses from various occasions.

Considering my particular interest in the legacy of Catherine Booth, in this biography, Booth-Tucker, Catherine’s son-in-law, provides valuable firsthand information about the historical and theological contexts of Catherine Booth’s contribution to establish the basis of female ministry (Chapter 12, “Woman’s Rights. 1853” and Chapter 32, “Mrs. Booth’s First Pamphlet. 1859” in Volume 1) from the early period of the Salvation Army movement as well as her holiness experience and her understanding of Wesleyan holiness theology (Chapter 37, “Mrs. Booth on Holiness” in Volume 1).

Regarding Catherine Booth’s experience of holiness, it is evident that from her earliest years, Catherine strove after holiness before God. At the age of eighteen (1847), she wrote in her diary:

My chief desire is holiness of heart. This is the prevailing cry of my soul. Tonight ‘sanctify me through Thy truth – Thy Word is truth! Lord, answer my Redeemer’s prayer. I see this full salvation is highly necessary in order for me to glorify my God below and find my way to heaven. For ‘without holiness, no man shall see the Lord!’ My soul is, at times very happy. I have felt many assurances of pardoning mercy. But I want a clean heart. Oh, my Lord, take me and seal me to the day of redemption.

As we see here, young Catherine declared her “chief desire” of life is “holiness of heart,” and she fervently desired to have it as the stage of full salvation from her early childhood. From her way of referring the certain terms such as “full salvation” as synonymous with the notion of “holiness of heart” or “a clean heart,” it seems evident that her understanding of holiness was already grounded in the Wesleyan tradition. In considering Catherine’s inheritance of Methodism, Booth-Tucker points out that “Kate and her mother were deeply attached to Methodism. Its literature was their meat and drink; its history was their pride – its heroes and heroines their admiration.” Methodists’ happy experiences of holiness and devotion appeared to her as a possible reality and the “higher idea.”

Regarding Catherine Booth’s foundational stage of spiritual formation, Booth-Tucker describes that although “Catherine’s school experiences were of comparatively brief duration,” in her later years, Catherine “acquired an extensive knowledge of church history and theology.” Her important readings included works by Wesley, Finney, and Fletcher. Catherine especially appreciated Finney’s theological works and agreed with the “new measures” of revivalism that he was noted for. Reading these works would help to formulate the theological foundations of The Salvation Army. Booth-Tucker affirms the fact that the most significant mentors of the Booths would include James Caughey (c. 1810-91), Charles G. Finney (1792-1875),[1] and Phoebe Palmer (1807-74). The latter were American revivalists, as well as John Wesley’s Methodist movement.

It is significant to recognize that Catherine Booth was inspired by the living example of the American holiness female preacher, Phoebe Palmer, known as the “Mother of the Holiness movement.” The pamphlet on Female Ministry; or, Woman’s Right to Preach the Gospel (1859), was produced in the response of the Rev. Arthur Augustus Rees’ attack on Mrs. Palmer’s right to preach the gospel. Along with responding to these unjust attacks on Palmer, the views expressed in the pamphlet were based on a theology of women in ministry that had emerged during her childhood education as well as debate in correspondence with William Booth during their engagement.[2]

As Booth-Tucker expresses her life journey until her final day on the earth of October 4, 1890, Catherine Booth poured out her unflinching prophetic vision and inspiration into the shaping of The Salvation Army. Catherine would write to her daughter, Emma, years later, that, “We are made for larger ends than earth can encompass. Oh, let us be true to our exalted destiny.” Catherine Booth was most certainly made for a destiny whose effects are still being experienced in the 21st century, especially through her prophetic contribution to female ministry and her teaching of holiness.

[1] Regarding the influence of Finney to Catherine Booth, Booth-Tucker pointed out that “Finney was to Mrs. Booth what Wesley had been to the General. Without agreeing with him on every point, she appreciated his massive intellect, enjoyed his lawyer-like logic, dived into the depth of his philosophy, and above all, admired the zeal and Holy Ghost power which permeated the life and writings of the great revivalist. Among the few modern books which have received the hearty ‘imprimatur’ of the Salvation Army have been the Revival Lectures and Autobiography of Finney…Finney….she considered to be a sound champion of the truth…As the controversialist, Finney was inimitable, smiting the errors of Calvinism, Antinomianism, and Universalism hip and thigh, with a trenchancy and power that left little to be desired. Mrs. Booth studied his writings perhaps more than those of any other author, and continued to do so, and to recommend them to others, to the end of her life…While Bramwell was resting in Scotland Mrs. Booth sent him the large volume of Finney’s Theological Lectures-undoubtedly the author’s masterpiece-urging him to use his leisure in studying them” (Booth Tucker, The Life of Catherine Booth, Vol . 2., 149-150).

[2]See Booth-Tucker, The Life of Catherine Booth, Vol. 1., 117-129, 339-380 and Harold Begbie, The Life of General William Booth, 2 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1920), Vol. 1., 245-50. It is important to note that William Booth’s early view on female ministry did not fully support that of Catherine. For instance, William Booth’s response on April 12, 1855 to Catherine was not exactly what she expected to hear from her future ministerial partner. William Booth responded: “I would not stop a woman preaching on any account. I would not encourage one to begin. You should preach if you felt moved thereto: felt equal to the task. I would not stay you if I had power to do so. Altho’, I should not like it. It is easy for you to say my views are the result of prejudice; perhaps they are. I am for the world’s salvation; I will quarrel with no means that promises help” [Italics in original] (Begbie, The Life of General William Booth, Vol. 1., 236; Cited in Dale A. Johnson, Women In English Religion, 1700-1925 [New York: The Edwin Mellen Press], 340 ff).

For more in this series, click here

written by Major Young Sung Kim, Territorial Ambassador for Holiness, Spiritual Life Development Department, USA East