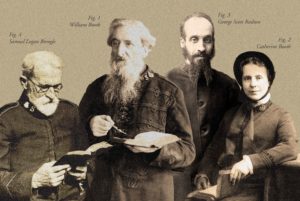

4 Key Salvation Army Biographies

4 Key Salvation Army Biographies

That Uncover Our Treasures

Part 4: Samuel Logan Brengle

Rightmire, R. David. Sanctified Sanity: The Life and Teaching of Samuel Logan Brengle. Revised and Expanded Edition. Wilmore, KY: The Francis Asbury Society, 2014.

David Rightmire’s Sanctified Sanity: The Life and Teaching of Samuel Logan Brengle is a well researched scholarly treatment on the life and ministry of Samuel Logan Brengle (1860-1936) in focusing his biographical assessment as well as his theological influence and contribution for enhancing the Salvation Army’s distinctive Wesleyan holiness teaching in relation to the context of the 19th–century holiness movement.

The first American-born Commissioner, Samuel Logan Brengle, known as the apostle of holiness, is a treasure of The Salvation Army both for his literary contribution in developing the Salvation Army’s holiness doctrine as well as his immeasurable influence of sanctified life ministry in the larger context of the international ministry of The Salvation Army.

Commissioner Brengle wrote nine books on holiness in his lifetime as gifts for the people’s spiritual life. Reading Brengle’s books is an experience of blessing not only for nurturing one’s soul for a holy living but also for understanding Brengle’s Wesleyan-distinctiveoctrinal teaching of holiness. The list of Brengle’s primary writings is as follows: Helps to Holiness (1896), Heart-Talks on Holiness (1897), The Way of Holiness (1902), When the Holy Ghost Is Come (1909), The Soul Winner’s Secret (1903), Love-Slaves (1923). Resurrection Life and Power (1925). Ancient Prophets: With a Series of Occasional Papers on Modern Problems (1929), The Guest of the Soul (1934).

Rightmire’s Sanctified Sanity is constructed in two main divisions, which are sustained with fifteen sub-chapters. In the first division, under the title, “Brengle’s Life and Ministry,” Rightmire carefully navigates us to explore Brengle’s biographical accounts. Although it was not the author’s main purpose to fully develop a comprehensive biography of Brengle, the reader will find sufficient biographical research to grab an in-depth understanding of Brengle’s life journey in context. Especially in part 1, the reader will be able to learn some important background understandings of Brengle’s conversion and sanctification experiences and his unique ways of developing a keen relationship with The Salvation Army.

In the second division, under the title “Brengle’s holiness theology,” Rightmire provides the reader with an “orderly account” of Brengle’s doctrinal teaching on holiness, particularly, in terms of how Brengle understood the role and scope of the Holy Spirit in the work of sanctification of the believer based on his reinterpretation of soteriological and pneumatological emphasis of the nineteenth-century transatlantic revivalism.

In this systematically organized and well-researched part in focusing on Brengle’s indispensable influence and contribution of holiness teaching, the author helps us to learn and affirm the essential aspects of Brengle’s Wesleyan holiness teaching by using layperson’s terms.

First, Brengle’s holiness theology is firmly grounded in the synergistic notion of the Arminian/Wesleyan soteriology apart from the Calvinist doctrine of salvation. Second, as the nineteenth-century Wesleyan holiness movement seems to emphasize a definite aspect of crisis experienced in the process of salvation and sanctification, Rightmire asserts that Brengle was more interested in bringing a balanced view of both/and not either/or between critical (crisis) and progressive (process) as a way of understanding its process of sanctification which is a valuable point itself.

Third, Brengle stressed the concept of the baptism with (or “of”) the Holy Spirit, which is a synonymous term of “second blessing” as a definite moment for entire sanctification. Fourth, the influence of Phoebe Palmer’s teaching on holiness is evident in Brengle’s writings, especially her concept of “altar phraseology.” Fifth, Brengle recognized that waiting on God as the fundamental spiritual principle in various stages of the Christian journey is never easy, but “a necessary part of the emptying and filling process of entire sanctification.” Sixth, considering the eschatological emphasis of the nineteenth-century holiness movement, Brengle’s eschatological position seems to lean toward the postmillennial view with a continued dispute for premillennialism. For Brengle, it is evident that his eschatological writings support the postmillennial position.

Finally, the theological distinctiveness of the nineteenth-century holiness movement is shown its gradual inclination to emphasize the theme of “the power,” rather than maintaining the balanced view of emphasizing the theme of “cleansing from sin” as the consequence of the baptism with the Holy Spirit. For example, Phoebe Palmer had inclined toward emphasizing a theme of “the power” in the later years of her holiness teaching.[1] One of the significances of Brengle’s teaching on holiness is to bring us into the balanced view of the work of the Holy Spirit which not only emphasizes on the aspect of empowerment but also on the “cleansing from sin (clean heart)” as the consequences of the work of the Holy Spirit.

Rightmire’s book, Sanctified Sanity, is an invaluable and critical resource for deepening our understanding of Brengle’s legacy of holiness teaching and his unalloyed passion for holy living.

[1] See Young Sung Kim, “Holiness is Power: Sources and Implications of Phoebe Palmer’s Holiness Theology,” Word and deed: A Journal of Salvation Army Theology and Ministry Vol. 14, No. 2 (May 2012): 29-49, http://www.thewarcry.org/files/2019/01/Word-Deed-14.2-May-2012.pdf

For more in this series, click here

written by Major Young Sung Kim, Territorial Ambassador for Holiness, Spiritual Life Development Department, USA East