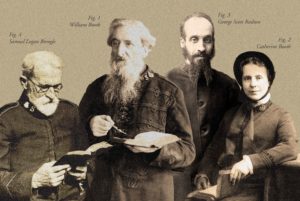

4 Key Salvation Army Biographies

4 Key Salvation Army Biographies

That Uncover Our Treasures

Part 3: George Scott Railton

Watson, Bernard. Soldier Saint: George Scott Railton, William Booth’s First Lieutenant. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1970.

Although many in the Salvation Army community acknowledge the significant influence of George Scott Railton (1849-1913) during the primitive period of the Salvation Army movement, very little theological or historiographical reflection has been done on the legacy of this “William Booth’s first Lieutenant” or The “St. Francis of The Salvation Army.”

Besides Eileen Douglas and Mildred Duff’s hagiographical account of George Scott Railton, entitled, Commissioner Railton (1920),[1] Bernard Watson’s Soldier Saint: George Scott Railton, William Booth’s First Lieutenantwhich contains significant portions of original materials brings to us a reliable and refreshing interpretation of Railton’s life and the ministry which made the inevitable influences in the early formative period of the movement. Watson insists that “it is doubtful whether The Salvation Army would have come into existence without George Scott Railton’s guidance in the crucial years 1873 to 1880.”

In his biography, Watson provides many significant biographical factors on Railton’s life journey. For example, Railton was a Methodist inherited convert who joined the Salvation Army and lived in the Booth home for eleven years. The Founder William and his wife, Catherine Booth, treated him like a son. He was a big brother to the Booth children and a mentor for Bramwell Booth, the elder son who became the immediate successor of the Generalship after his father’s death. The Booth family loved him and relied upon him in many aspects of ministerial companionship.

Railton became the Army’s first Commissioner, who had a better educational background than his colleagues at that time. Railton was “a linguist, a prolific writer” and the only male leader of the Army’s first official “invitation overseas” to the United States with seven “Hallelujah Lasses.” Particularly, Railton was the hidden one who had inevitably influenced not only to frame “many of the movement’s Order and Regulations,” but also “to set out its first doctrines and to have made radical and highly successful contributions to Salvationist tactics.” Railton’s influence was decisive on William Booth’s final decision for abandoning the traditional practice of the sacraments in the Salvation Army. It was also Railton who formulated the first edition of The Doctrines of The Salvation Army: Prepared For The Training Homes, which manifested the Salvation Army’s primitive theological foundation of Wesleyan holiness revivalism.

At the same time, the author unveils the sensitive and complicated sides of the relationship between the Booths and Railton himself. Watson indicates that “in the climate of the early twentieth century the record could not reveal that the same Commissioner Railton who was revered for his saintly life – “the St. Francis of The Salvation Army” – had publicly protested against Army policies, fallen from the General’s favour and persisted in disapproval of new methods adopted by his son Bramwell, the chief of the Staff.”

Commissioner Railton was promoted to Glory in 1913, one year following the death of General William Booth, and he was buried next to the founder’s grave as his ever-faithful lieutenant.

[1] Eileen Douglas and Mildred Duff, Commissioner Railton (London: The Salvation Army Publishing and Supplies, LTD, 1920).

For more in this series, click here

written by Major Young Sung Kim, Territorial Ambassador for Holiness, Spiritual Life Development Department, USA East